The whole study of economics is based on one fundamental problem: i.e. people have a large, and growing, demand for commodities whereas the resources to meet this demand are scarce. There aren’t enough resources to satisfy demand. This fundamental problem gives rise to other questions, such as,

- What should be produced – that which is useful or that which is profitable?

- Which consumers should benefit – those who afford a commodity or those who are in need of it?

- Are there any commodities that should be available to all irrespective of their personal income?

- Are there any commodities that should be discontinued irrespective of their profitability?

These questions have largely contributed to three types of economies, i.e. those which shift towards the theoretical extremes of a Planned Economy or a Free Economy, and those adopting a “Mixed” system.

In order to illustrate these three economic systems, we shall start by defining the players. An economy is made up of

- Households: These include private, corporate or government entities in their role as consumers

- Firms: These include sole traders, partners, corporate, private and/or government establishments who provide a good or service (collectively known as a commodity)

- The Government: The Government plays a pivotal role in any economic system because it is a major consumer, a fiscal authority, a regulator and can also be a supplier.

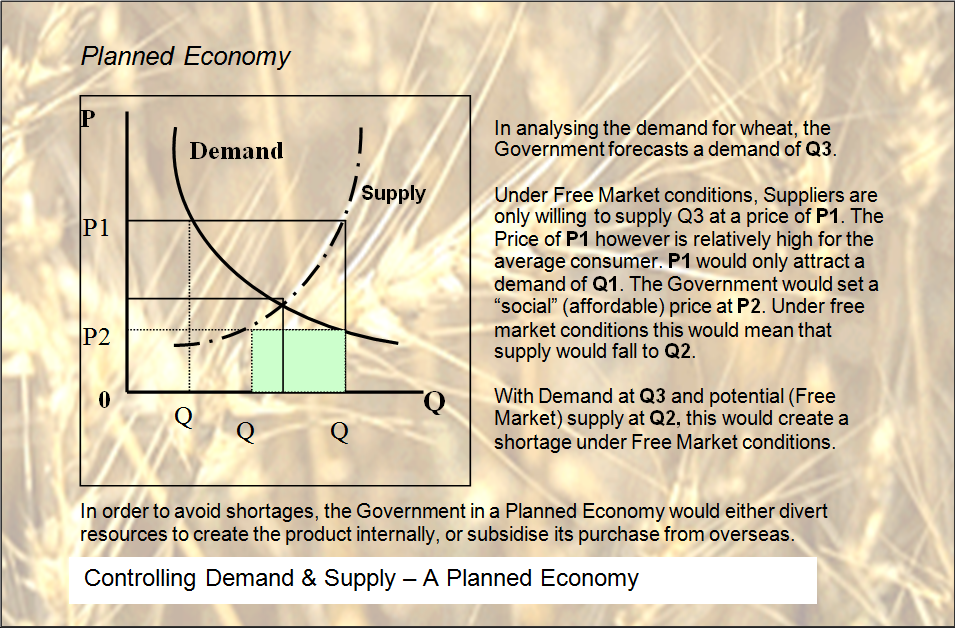

A Planned Economy, as the name implies, is a theoretical extreme where the Government takes all decisions relating to the economy. The Government decides how, what, when and how much to produce and what pricing and consumption levels to set. The economic systems closest to this model were the ones in the Eastern Bloc before the fall of communism and that of Cuba.

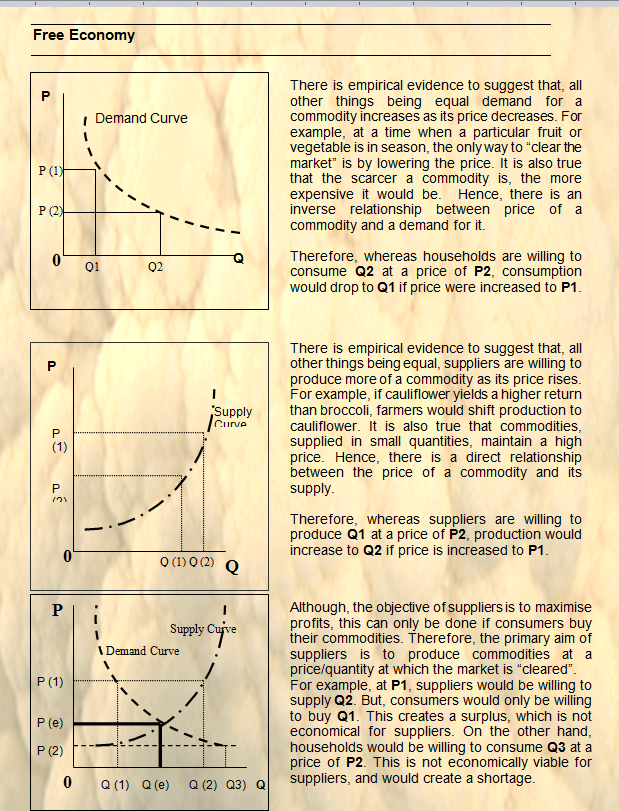

The diagrams that follow help to illustrate these two systems:

Some assumptions have been made in plotting the above graphs. The more prevalent of these are listed in the above illustrations, namely:

All things remaining equal (ceteris paribus), households consume more as the price goes down and less as the price increases. This is referred to as an inverse relationship between Demand and Price.

Ceteris Paribus – suppliers are willing to supply more for a higher price than they are for a lower one. This is referred to as a direct relationship between Supply and Price.

Changes in price result in movements on the Demand and/or supply curve. These, in turn “settle” on an equilibrium price, i.e. a price at which the market is “cleared” of the commodities.

Price is, therefore, the main determinant of supply and demand in an economy.

There are other factors that influence demand. These include:

Income: If the income level of a household changes, it means that the household, now, affords more at the same price. It may also affect the tastes of the household. The household may shift from one commodity to say, a similar one but of a higher quality, as a result of an increase in income.

Taxation: Changes in taxation can make a product cheaper or more expensive. For example, an increase in the rate of customs duty would result in an increase in the price of an imported commodity.

Price of Substitutes and Complements: If the price of substitutes increases, demand for a commodity falls. If, for example, the price of margarine increases, this would have an opposite effect in the demand for butter, as households consume less margarine. On the other hand, in the case of complements, as the price of a complement increases, demand for a commodity falls. If, for example, the price of diesel increases, demand for diesel cars drops. There is an inverse relationship between the price of complements and the demand for a commodity.

Demographic Changes in an economy also have an impact on demand and supply, irrespective of the price. Changes in, say, the age and/or sex structure or population distribution within an economy would directly effect demand.

There may also be other considerations, be they social or political that can give rise to changes in demand.

The main factors effecting supply besides prices are changes in Factors of Production that have a direct impact on production costs. New technology means that commodities may be produced at a cheaper rate. Therefore, at the same cost, more is produced.

Having outlined the theoretical extremes of a Free and Planned Market economy, the other, more realistic economic system to view is the “Mixed” economy. The Price Mechanism of a Free Market system is certainly the most efficient system of distribution. A price is set at a level at which the market is “cleared” of commodities. However, although it is an efficient means of distribution, it is not always the fairest or most appropriate. There are commodities that, by their very nature have to be controlled by the central authority in an economy. For example:

Justice cannot be available only to people who can afford it.

Defense is essential for the stability of a country irrespective of its cost.

Education, healthcare and social security should not be distributed only to people who can afford it. Their availability now would have an impact on the economy in the future.

Also there are industries, which, for various reasons, the government would wish to preserve irrespective of their profitability. This is done either through price control or subsidies. Although this may be seen as a distortion of an otherwise efficient distributor of resources, government intervention is, nonetheless, required in the above instances for the common good of a society.

Therefore, a Mixed System is essentially a Free Market system with Government intervention in specific areas mainly for reasons of social, justice and/or defense reasons. This intervention often results in commodity shortages (such as in the case of rent laws in welfare states) or commodity surpluses (a typical example is the Butter or Dairy Mountains as a result of the E.U.’s agricultural policies) in the long run.

Having mentioned the determinants of supply and demand, another important aspect to consider is how the gradients of the demand and/or supply curves are established. In other words, by how much would demand for a commodity change if its price or the price of a substitute/complement changes? This is known as the Theory of Elasticity.